Here's some stories on the various instruments we enjoy. We give you some instrument history, plus our personal history with them. You can go to the Listen page to view some video samples.

Celtic Harp Celtic Harp (Irma 2011) Celtic Harp (Irma 2011)Various forms of fixed tuning harps have been around for at least 5000 years. A major limitation was that if you wanted to play in a different key, you had to retune the harp. Celtic harps (aka lever harps, folk harps) were introduced in the 16th or 17th century with hand-actuated sharping levers near the top of individual strings which permitted the instrument to be played in different keys without retuning. Raising a lever raises a string's pitch by half a step. The ability to play in several different diatonic scales (just the notes of particular scales) opened a vast world of music that could be played, and being able to play an occasional accidental note on the fly expanded the repertoire even further. Folk harps come in different sizes, small (lap, travel, and therapy harps), medium, and floor models ranging from 16 to 40 strings with a total string tension from 700 to 1000 pounds for full size models. Standard folk harps can also be called nylon-string folk harps because the higher-pitched strings are nylon monofilament which are common between builders. There is no standardization on what materials are used for the lower-pitched strings: nylon core with nylon or wire wrappings, synthetic gut, fluourocarbon, or compound (complex) materials. Uncommon folk harp variations include double-strung harps, cross-strung harps, wire-strung harps (as opposed to nylon string, also called Irish harps) and Paraguayan harps which originated in Venezuela. Celtic harp music has been an important emblem of Irish nationalism since the 10th century. With harp music being viewed as a key component of the Irish and Scots' national identity and harpers being the purveyors of oral history, the British monarchy tried to eliminate harp playing beginning in the early 1500s. In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I ordered all Irish harpers to be hung and their harps burned. Ah, but at the same time, she loved the music and kept a harper in her court. Beginning in 1650, Oliver Cromwell ordered all harps throughout Ireland to be burned and harpers were forbidden to congregate. We are blessed that the instrument and some of its music survived in various forms.  Lever Harp vs Pedal Harp Lever Harp vs Pedal HarpWith continued development, the modern, fully chromatic pedal harp (aka concert, symphonic, or orchestral harp) was invented in 1820 by Parisian maker Sébastien Érard where he introduced 7 pedals (one for each note of the scale no matter which octave) and a complex system of wire cables, cams and pulleys (all hidden inside the pretty wood frame) to provide a fully chromatic instrument (all the white and black notes) that could play in any key with all accidentals easily available. In contrast to approximately 4.5-octave/20-30 lb lever harps, pedal harps normally have 40-47 strings (as much as 6.5 octaves), 75-90 lbs, with a total string tension over 2000 lbs. (Irma) In late summer of 2001, Scott and I decided to visit a local music store we hadn't explored before. There, along one wall, stood a number of harps. As I looked at each one, stroking the beautiful woods, listening to the quiet tones, the store owner saw my interest and asked if I had any questions. I looked at the different colors of strings, and said, "How do you know where you are?" Of course, he was only too happy to explain! (C strings are typically red, F strings can be dark blue or black.) I signed up for brief group classes, and had bought my first harp in time to play for Christmas! I was hooked, fascinated, enchanted. It's easy to see the large pedal harps and be intimidated. The intimacy of playing a smaller harp is amazing. My 33-string Hidden Valley extended-soundboard harp and I bonded that year over beloved Christmas carols, but it was when I learned Greensleeves that I knew I would love playing for the rest of my life. I've also had Dusty Strings harps. Within a couple of years, I found myself teaching Celtic harp, focusing on students with little or no music background and unable to read music. It is so rewarding to watch others fall under the spell of the magical harp. |

Mountain Dulcimer Mountain Dulcimer (Irma 2011) Mountain Dulcimer (Irma 2011)Because the mountain dulcimer and hammered dulcimer have the same name, people often get them confused. That's if they've even seen one or the other before. Be assured, they are entirely different instruments. Both being of the zither family where the strings run the full length of the instrument bodies (unlike guitars and other things that have necks that extend beyond the body), that's pretty much where the similarities end. Hammered dulcimers are played by striking the strings with small mallets or hammers. Like a guitar, a mountain dulcimer is played by picking/strumming strings or by finger picking with the right hand and fingering chords and notes on a fretboard with the left hand. Unlike guitars and other more common fretted instruments, the mountain dulcimer doesn't have all the frets, it's missing some. Whereas guitars, mandolins, and banjos are chromatic with frets every musical half step, the mountain dulcimer is primarily diatonic (just the notes of a particular 7-note scale) with a few additions. Traditionally, it's hourglass in shape, but can also be teardrop or boxy. The German Scheitholt that arrived in America in the early 18th century is thought to be the predecessor of the mountain dulcimer (also called Appalachian dulcimer or lap dulcimer). The mountain dulcimer originated in early 19th century Appalachian Scotch-Irish communities, one of the very few instruments invented in America. Though there were a few examples of commercial makers prior to the late 19th century, mountain dulcimers for the most part were made by individuals supplying their families and close neighbors with instruments. Folk musician Jean Ritchie (1922-2015) brought the instrument to the world stage in the 1950s with her music and literature. You usually see what we refer to as "standard" dulcimers, but there are also soprano, baritone and bass range instruments, dulcimers with banjo heads (I have a Mike Clemmer solid body nylon-string BanJammmer as shown below) and even other variations. Dulcimers usually have 3 strings where one "string" (the melody string) is composed of two strings spaced closely together like you see on mandolins. Some players dispense with the extra string. Dulcimers can also be set up to have 4 equidistant strings for more complex picking patterns and chords, and I even have a 6-string dulcimer (3 sets of dual-string courses) which sounds like a 12-string guitar, only "dulcimerish". While I use microphones or internal acoustic transducers to amplify my mountain dulcimers, their are also dulcimers with magnetic (i.e. electric guitar) pickups and even solid body electric dulcimers with the wildest paint jobs you can imagine.  Mountain Dulcimer-Banjo (Irma 2020) Mountain Dulcimer-Banjo (Irma 2020)(Irma) I've often teased, especially when visiting areas of the country teeming with dulcimer players (both kinds), that Albuquerque is far from being the dulcimer capital of the world. While the western US has small pockets of players, there are very few festivals. I missed the experience of growing up in Arkansas, but my older siblings lived on the farm in an area where my family goes back generations. For whatever reason, my family's music traditions included fiddles, guitars, banjos, mandolins, but not dulcimers. My sister was given a mountain dulcimer one year. It ended up as a wall decoration. Sound familiar? Because I had only a few experiences hearing the mountain dulcimer, in my ignorance, I didn't view it as a "serious" musical instrument. Fall of 2005, Scott bought me a quality mountain dulcimer for our anniversary. The following month we made it out to Oklahoma for our first dulcimer festival (Russell Cook's last Sawdust Festival). This was my first experience seeing nationally acclaimed mountain dulcimer players, and I was greatly impressed by the demonstrated skills, and the beauty and versatility of the instrument. I was hooked! Here in Albuquerque, I viewed one of my friends, Michael Carlson, as the Pied Piper of mountain dulcimer in New Mexico. He encouraged so many people, young and old, to start playing, and was a passionate promoter of the instrument. He was teaching a mountain dulcimer group class when he had a recurrence of cancer. Knowing my teaching experience and love for music, he asked me if I would finish the class for him. (What a baptism by fire, being an inexperienced dulcimer player myself at the time.) Michael passed away before I completed his class. Thus began my journey falling in love with the mountain dulcimer. I have envied those of you in areas where teachers abound, where there is such a rich tradition of dulcimer music. Since we didn't have advanced instructors locally, we started driving to festivals: Steve Eulberg's Colorado festival in February, the Mountain View, Arkansas Dulcimer Jamboree in April, and Dana Hamilton's Glen Rose, Texas festival in May. In September 2011 we made it to the Walnut Valley Festival in Winfield, Kansas, for our first time which was absolutely amazing - we call it the national acoustic festival - every western acoustic stringed instrument you can think of. Dulcimer festivals have been a wonderful experience for us, and never fail to inspire me to try new styles and techniques in my own arranging. A few of us here in New Mexico came up with the idea of bringing the best dulcimer performers and teachers in the Nation to us here in Albuquerque: we started the New Mexico Dulcimer Festival in 2010! |

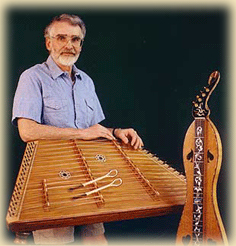

Hammered Dulcimer Hammered Dulcimer (Scott 2017) Hammered Dulcimer (Scott 2017)Music instruments where you strike strings with sticks (hammered dulcimers) have been prevalent in many cultures under many different names: cimbalom (Hungary, Rumania, Ukraine), cymbaly (Poland), hachbrett (Austria, Germany, Switzerland), khim (Cambodia, Laos, Thiland), salterio (Brazil, Italy, Mexico, Portugal, Spain), santoor (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan), santouri (Greece), santur (Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Turkey), tiompan (Ireland), tsimbl (Yiddish), tsymbaly (Belarus, Ukraine), yangqin (China), etc. A common claim is that the hammered dulcimer originated in Persia (modern-day Iran), then was brought to Western Europe between 900 and 1200 by the Moors and returning Crusaders. However, in impeccable research by Paul M. Gifford (Master's Degree in Library Sciences/M.L.S., Senior Associate Librarian Emeritus, Genesse Historical Collections Center, University of Michigan-Flint), the instrument as known today is believed to have been developed independently in Europe in the early 15th century when the technology of drawing wire was matured resulting in uniform cross-section wires without weak spots. Early gut strings or beaten wire strings worked for plucked instruments but would break under the forces associated with striking. By the early 16th century, the hammered dulcimer was firmly established in Europe and was popular in the court of King James I of England. It was brought into eastern Europe by the Roma people. The harpsichord was one of the most important keyboard instruments in European music from the 16th century through the first half of the 18th century. Its main limitation was that the string plucking mechanism provided the player no control over loudness note-to-note, nor tone quality. Being struck by hand-held hammers, the hammered dulcimer provided dynamic control of volume and tone. Based on the hammered dulcimer, Italian harpsichord builder Bartolomeo Cristofori invented the pianoforte in the early 1700's where strings were struck by hammers using an ingenious and complex key mechanism. The harpsichord was gradually replaced by the pianoforte then the modern piano, with the transition complete by the early 19th century. Also based on the hammered dulcimer, Hungarian Josef Schunda invented the concert cimbalom in 1874 where strings are struck by hand-held hammers.  Lots of strings! (Scott 2008) Lots of strings! (Scott 2008)To eliminate confusion with eastern European and Asian instruments with different note layouts, the instrument I play can be called the western hammered dulcimer. Hammered dulcimers are characterized by bright, bell-like tones with lots of sustain, although some builders are providing low-sustain models. The first recorded sighting of a hammered dulcimer in America was in Massachusetts in 1717. By the 1850s, they were being produced commercially in New York. Montgomery Ward started listing hammered dulcimers in their catalogs in 1894, and Sears by 1897. Because it was much more portable than the piano, the hammered dulcimer was popular in 19th century lumber camps (sometimes called a lumberjack piano). As reed organs and pianos became affordable, American interest in the hammered dulcimer sharply declined beginning around 1906. The dulcimer had a brief revival beginning in the 1920's through car mogul Henry Ford's love of social music. Ford's Early American Orchestra played for dances in Michigan, released recordings on the Victor and Columbia labels, and aired a weekly national radio program. With a particular admiration for hammered dulcimer, his orchestra always include several. With Ford's death in 1947, the orchestra disbanded and interest in the dulcimer waned once more. The 1960s folk revival inspired new builders to start making dulcimers again which reintroduced the instrument worldwide.  Various Hammers Various HammersThe sticks you strike the string courses with are called hammers, thus the instrument's name. Hammers are usually made out of wood, but are also available out of metals and even carbon composites. Hammers may be single sided, double sided (often with one side bare wood and the other with some kind of padding for a softer sound), and with both rigid and flexible shafts. Dulcimer hammers for instruments from other cultures can differ radically from these designs. |

Dulceleste (Dulcimer Celeste) Celeste showing gray metal tone bars While uncommon, there are a few variants to the standard stringed hammered dulcimer. I have acoustic pickups mounted in my regular dulcimer, but they sound similar to using a microphone. Some builders have created "electric" hammered dulcimers, with or without soundboards, where string vibrations are picked up by various pickup schemes then routed to outboard electronics including standard electric guitar effects pedals. A couple of builders are making dulcimers where hammers strike small-diameter metal rods rather than steel string courses (sometimes called hammered mbira). If you've ever looked inside a Fender Rhodes electric piano, they use a similar technique for sound production. I had been aware that there were a few "hammered dulcimers" built where hammers struck flat metal tone bars rather than steel strings, providing a sweet bell-like tone that would be wonderful for some of our Christmas arrangements. Although I searched for something like this for years, I was unsuccessful finding anything for sale for a long time.  Rizzetta Dulceleste (Scott 2022) An orchestral celeste (sometimes called a bell piano) uses a piano keyboard action but hammers strike tone bars mounted in the instrument's case rather than strings. Taking the idea of the glockenspiel or orchestra bells, internationally-renown hammered dulcimer (and other instrument) builder Sam Rizzetta built a small number of instruments with the note layout of the western hammered dulcimer on a lightweight resonant frame (no resonator tubes) where the player strikes aluminum bars rather than strings. Because its sound production is like that of a celeste (think of the Nutcracker's Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood theme song, or the Harry Potter movies' Hedwig's Theme), he named it the dulceleste. When Sam passed in 2021, I learned that his protégé, Nick Blanton (also of West Virginia, and an esteemed instrument builder himself) was helping Sam's wife, Carrie, sell some of Sam's instruments. There were two dulcelestes up for grabs with one already spoken for. I was fortunate to be able to purchase the larger of the two in a size similar to standard hammered dulcimers. It does not provide the same feel as a regular dulcimer's "bouncy" strings, so a lot of the regular playing techniques don't work. I've also had to experiment with different hammer designs, and added a 46th tone bar for a note that is normally missing in the standard layout which I wanted. We have loved integrating it into our music.  Sam Rizzetta Sam RizzettaSam Rizzetta (1942-2021) began building guitars and banjos in his youth, eventually adding carving and mother-of-pearl and abalone inlaying. In addition to building and repairing common string instruments, he started building fretted (mountain) and hammered dulcimers. He formed the early 4-member hammered dulcimer band, Trapezoid, in 1974, designing a family of hammered dulcimers from soprano to bass. Many of us coming to hammered dulcimer learned from listening to his 15 solo or Trapezoid albums. All contemporary western hammered dulcimers incorporate design innovations he introduced. Sam spent decades teaching instrument building, and several companies are licensed to build his designs. Performance credits included the Kennedy Center and the National Cathedral. Sam was nominated for a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship for lifetime achievement in the arts. |

Guitars 6-string nylon (Irma) & 12-string steel (Scott 2006) (Irma) I can't remember a time when singing and playing the guitar wasn't a part of my life. Mom taught me and my two sisters to play guitar, and we'd learn the popular songs by ear, listening to the radio or record player. Early on, my hands were too small to fit around the neck of the guitar, so mom would tune it to an open-G, and I'd use a wooden pencil to chord it like a dobro. In fifth grade, my home room teacher had a guitar class that met after school, and I would stay and play along. By that time I didn't need mom to retune the guitar, and had my own favorite songs to learn. When I'd get 'stuck' trying to figure out a chord, mom would bluntly tell me to listen and work to find just the right one. She wouldn't tell me what chord would work, she'd make me find it for myself! I would listen to Judy Collins and dream of growing up to sound just like her. Gordon Lightfoot, John Denver, I fell in love with ballads, and enjoyed playing and singing stories that would capture the imagination, just like reading a good book. My first guitar student was my best friend in sixth grade. She wanted to play guitar with me, and her parents bought her this huge 12-string. She had to work so hard to press down those strings with her young hand. But she learned quickly, and we shared many hours of music together. Little did I know that five decades later I would still be teaching people to play and sing with their guitars! Growing up, my favorite guitar was a German folk guitar - nylon string but braced differently than nylon string guitars in America and with a narrower neck. Most of our instruments we bought in Germany didn't like transitioning to the New Mexico desert after Dad retired from the Army, and the guitar eventually became unplayable. While I played steel string guitars in the interim, I eventually found a lovely used nylon string guitar (non-classical, same model Willie Nelson plays) which I'll play for the rest of my life. To add texture for CDs, I'll still play steel-string guitars occasionally. And did I mention, Scott got me a pink solid body electric guitar at a point in time with open-coil humbucker and "lipstick" single coil pickups! It's from Daisy Rock Girl Guitars, a company founded in 2000 by L.A. rocker Tish Ciravolo who's product line includes shorter/narrower neck guitars for smaller hands in styles and colors attracting both professional female players and teen girls that needed a more inviting experience. We both worked up some tunes on electric guitars for a Zoom open mic with friends around the country that began when everything closed down during the pandemic.  Electric Guitar (Scott in High School 1976) (Scott) My two oldest brothers graduated high school in the 1960s, and listened to lots of the Beatles, Santana, The Who, Cream, The Rolling Stones and other guitar-based groups. I remember when one of them bought a junkie used electric guitar, put a fantastic candy emerald green paint job on it with about a thousand coats of clear, and made a lot of noise playing it through my dad's stereo console (a huge piece of furniture stereo aficionado's would build to house early high fidelity equipment). This fad passed, and they grew up and left home. My closest brother had an acoustic guitar that he never did much with, and one day in 10th grade one of my good friends asked me if I wanted to learn to play. I was doing lots of vocal and keyboard music at the time, so I thought "why not?". I think she showed me perhaps 3 or 4 chords, and I was lit on fire. I bought my first guitar (a cruddy used 1969 Harmony H82 Rebel semi-hollow body electric) for $60 at a pawn shop, and my dad sprung $100 for a low end Univox amp which he promply upgraded with a better speaker.  Electric Guitar with Harp (2007) I would spend hours every day practicing just a single chord change, or doing lead rifts over and over and over. With a good group of friends, we'd play at school assemblies, and I also played a lot at church. The summer before college, I found a job doing architectural drafting (and I could do that at midnight), so I had an all-electric band named Sweetlife, and was playing guitar perhaps 8 hours a day. When I met Irma in college, she was leading a principally acoustic folk group that I started to perform with on electric guitar. Within a year, I was bit by the 12-string bug, and put a significant amount of effort into 12-string acoustic guitar for about 20 years until a severe wrist injury (non-music related) put that out of the running for the most part. We've always had steel 6-string guitars around, and I do a significant amount of playing on those. I loved the songs of the 1970s/1980s early Christian acoustic music artists which is where I learned a lot of my flatpicking and fingerpicking styles. In my early 40s, I got the bug to be playing electric guitar more (still playing my junky Harmony), and developed a fetish for vintage Gibson SG solid body electric guitars. I spent countless hours researching every model ever made, and trying to find a good example to purchase. In this timeframe, we had all our guitar repair work done by a wonderful luthier and performer, Dennis "Dill" Dillon. He challenged me on why I wanted to limit myself to the sounds you could get out of a SG, and started trying to convince me that I needed a dual voice guitar (dual humbucker electric guitar magnetic pickups with single coil capability plus piezo-electric under-saddle bridge acoustic pickups). It was nearing my birthday (planned event for a guitar purchase), and he sent me home one day with his silver leaf flamed maple Godin LGX guitar that he had customized as one of his personal instruments, just to "see" what I thought. He knew beforehand what the outcome would be. The guitar never returned to his store, and after 27 years of playing my cruddy Harmony, I bought a "grown up" electric guitar! We actually went through a phase where I played a lot of electric guitar (mellow jazz settings) with Irma on harp. Besides electric, 6-string and 12-string acoustic, there are a few tunes that I like to play nylon string guitar on. |

Banjo 5-string Banjo (Irma 2011) 5-string Banjo (Irma 2011)(Irma) When I was in high school, my dad sold enough at work to win a certain number of points toward a prize he could choose from a company catalog. He let Mom choose the prize. She decided upon a huge banjo that was so heavy we could barely hold it. Mom and I taught ourselves a few chords, and bought a strap so we could stand when playing. Wow. My neck would get sore and my left arm would fall asleep! While I played it occasionally through the years, I never really took to it due to the weight. Then, several years back Scott bought me a lightweight open-back Deering banjo without the resonator. Yee-haw! Finally I could enjoy playing the banjo without causing pain and numbness to various body parts! I took a few lessons in claw hammer style, that didn't really take. I then took a single lesson from one of Scott's work friends who plays Scruggs style, and that got me going. Steve Martin, I am not. While I found I didn't have a million hours to perfect my playing, I did learn a few rolls, numerous chords, and Foggy Mountain Breakdown. Enough to have a blast adding a bit of seasoning to our music repertoire. |

Mandolin and Octave Mandolin Mandolin (Irma 1977) (Irma) Mandolin was another one of the instruments that we had at home when I was growing up. My folks back in Arkansas played, along with guitars and fiddles. We had a lovely inlaid flat-back mando and a pear-back mando that we bought in Germany. I learned enough chords to play in all the popular keys. The great thing about the mandolin: it was small, and my hands just fit! My sisters and I would pick out a few tunes, but mostly we played chords when we were singing. With the climate change from Germany to New Mexico, they eventually dried up and became unplayable, so we've bought others to have around. I listen to people like Chris Thiele, and marvel that human hands can actually move that fast. |

Mandolin (Scott 1978) and Octave Mandolin (2010) (Scott) Growing up, I wasn't really exposed to bluegrass instruments or music, never thought about mandolin. My dad's father was a professional string band musician in Missouri who reportedly played anything and everything with strings, and my dad had a specific distaste for that style of music. Not for any aesthetic reasons, but because his bed was the living room couch, and when the band was over to practice, he couldn't go to bed when he wanted. He was a radio operator in World War II on Navy PBY Catalina and PBM Mariner flying boats, and my mom was an Army nurse. Their music was primarily big band, jazz, so mandolin just wasn't in my childhood experiences. In college, my roommate who was in Irma's band with me had a mandolin, and I had a few tunes I would play on it from time to time. Irma also had one from Germany that we'd play occasionally. As we got more and more into Celtic music, I developed a great appreciation for some of the fantastic bouzouki playing by folks like Andy Irvine of Planxty and Dónal Lunny of Planxty and The Bothy Band. I am also amazed by players like Chris Thiele and Sierra Hull. Because the long neck of a bouzouki exceeds the reach of my small hands, I ended up getting an octave mandolin instead. I keep it tuned to GDAE, just like a regular mando (but an octave lower). |

Fiddle Irma and Gretchen on dual fiddles (2009) (Irma) Two of my uncles were fiddle builders, so it has always had a certain allure for me. Frankly, the reason it took so long for me to get to the fiddle was because I had so many other instruments that I loved to play. Then I met Gretchen Van Houten. Gretchen is one of those people who have only to walk into a room and an ordinary rehearsal becomes a party. Long past the point that she has to prove anything to anyone (1992 National Fiddle Champion, Western Music Association fiddle champion), she'd calmly slouch into a chair, and proceed to blow us away. She didn't need music, she didn't even need to know the song. Gretchen's playing blew a breath of fresh air, not only into the tunes, but into my heart. She'd play along for a while, then all of a sudden, she'd lean forward, get this tiny little smile on her face, then promptly leave us all in the dust. Just because she could. And it was thrilling for us mere mortals. Watching her play inspired me to dig into my roots and tap that fiddle blood in my family. I can never thank her enough for her patience. While still a beginner, every now and then, when I'm sawing along on Bonaparte's Retreat or Faded Love, I can close my eyes and feel like I'm truly a 'real live' fiddler. You should hear my rendition of Boil Them Cabbage Down. Stunning. So it's a work in progress, but the love of playing is already there, just waiting for my hands and schedule to catch up. |

Bowed Psaltery Bowed Psaltery (Scott 2014) (Scott) Plucked diatonic psalteries have been around since Biblical times, but they are an entirely different beast than the modern chromatic bowed psaltery which has a characteristic triangular shape. You can sometimes see bowed psalteries at Renaissance fairs because they look like they "should be" really old, and they are even misreported as Medieval or Celtic in origin. However, the bowed psaltery (named streichpsalter in German) wasn't invented until around 1949 (I believe by Walter Mittman in Westphalia, Germany) where they were used as simple instruments to teach music to school children after WWII. They were brought to America (Atlanta, Georgia) in 1959 by George Kelischek, a master violin builder. He's a marvelous fellow I've been able to chat with a few times who founded the Kelischek Workshop for Historical Instruments in 1955 in Witten, Germany, where his work included designing and building bowed psalteries. He moved his workshop from Atlanta to Brasstown, North Carolina in 1970. While they haven't produced bowed psalteries since the 1980s, they continue to manufacturer scads of other well-received instruments to the present day (such as kelhorns, crumhorns, tin whistles, dolce-duo, recorders, pentacorders, tabor-pipes, txistus, gemshorns, ocarinas, hurdy-gurdies, plucked psalteries, vielles, violas da gamba and more).  Winter Harp's Bass Psaltery Unlike instruments in the violin family which have a curved bridge where you access "inside" strings by changing your bow angle and playing across the bridge, the bowed psaltery has a flat bridge. You play each string up and down the sides between the hitch pins, with the white notes (naturals) on the right side of the soundboard and the black notes (sharps and flats) on the left side of the soundboard. Thinking of the white key and black key layout of a piano, the psaltery's hitch pins on the right side are evenly spaced (the white notes), and the hitch pins on the left side are grouped in the expected pattern of 2 notes - 3 notes - 2 notes - etc. (the black notes). If you hang around the dulcimer community for very long, you'll eventually see a bowed psaltery. As they use similar hardware and building techniques as hammered dulcimers, there are a number of instrument builders who make both. |

Recorders and Whistles Recorders: Sopranino, Soprano, Alto, Tenor and F-Bass (Scott 2019) (Scott) With origins dating back to the late 1300s, recorders underwent significant technological improvements through the 18th century, far outclassing simple flute predecessors. Numerous Renaissance composers wrote works for the instrument, as well as familiar Baroque composers such as Purcell, Vivaldi, Telemann, Bach, and Handel. In the mid 18th century, interests in recorders waned with the introduction of modern keyed orchestral woodwinds. Perhaps foremost, transverse flutes had begun to be played by amateurs as they were acoustically more forgiving of design defects which could be overcome by embouchure tuning (how the player forms their mouth and lips) whereas recorders needed custom voicing maintenance by skilled craftsmen who were also experienced players. Recorders were revived in the 20th century when early music reenactors started playing original instruments and accurate reproductions. Interest surged in the 1970s due to lower-cost mass-produced models which encompassed quality wood and plastic historic reproductions fuelded by the Early Music Revival as well as inexpensive, easy-to-play plastic-sounding recorders for school children and curious adults. Recorders actually started being manufactured as early as the 1920s for educational use. Unlike modern woodwinds and horns that require learning proper embouchure (mouth formation), recorders use an internal duct or fipple design where the player blows into a mouthpiece to initiate sound waves, eliminating some of the challenges of other woodwinds. Regrettably, the recorder's reputation has suffered being viewed as an "easy" first instrument associated with elementary school music curricula using cheap imitations taught inexpertly. This has misrepresenting both the historical recorder's beauty and capability.  Dale Taylor with Renaissance Tenor Recorder We have a friend, Dale Taylor, who ran the national office of the American Recorder Society in New York City in the late 1970s. He has restored original early instruments, built museum quality reproductions of Renaissance and Baroque woodwinds, repairs harpsichords, and performs on recorders, traverse, cornetti, dulcian, shawms, sackbuts, rackets and other early winds. He teaches (and voices) recorders, early winds and modern trumpet and trombone, conducts early music ensembles, coaches chamber ensembles, and is recognized internationally as an author, instrument technician, performer, and historian. I tell you what, if you ever get to hear him play recorder, "easy instrument" would be the last thing to ever cross your mind. I had been interested in Renniasance and Baroque music instruments since a child. I played electric and pipe organs beginning at age four and was a nerd kid that enjoyed organ pipe physics. My interests in recorders was probably natural as their method of sound generation is identical to some organ pipes. One year for my birthday while in high school, my oldest brother gave me a pretty poor quality wooden alto recorder. I must have driven my family crazy with all the squeaks it took for me to learn how to play it.  Really Big Recorders (Royal Wind Music, Amsterdam) That was in the days before the internet, so I'd go to the Fine Arts Library at UNM and read everything I could lay my hands on concerning recorders. Within a year, I had bought a good quality plastic alto, and played a lot of folk and classical music on it, even jazz. There was a wonderful little music store here in Albuquerque years ago, run by John Truitt. John was a composer, flamenco guitarist, woodwind specialist, early music enthusiast, and educator. He founded Musica Antigua de Albuquerque. I was able to purchase a good soprano recorder from him in the early 1980s. In 2007, Irma bought me a tiny sopranino recorder that I'm having an absolute blast playing. It takes hardly any air, almost plays itself, and has such a sweet high tone. In the recorder family, there's one smaller recorder, pitched half an octave above a sopranino, called a Garklein or Sopranissimo. Even for my small hands, finger holes are way too close and it's not really practical for melodies. Recorder consorts might use it for sound effects! On the other end of things, I acquired a tenor recorder at a point in time, and when recording our 2019 Christmas album, I needed to buy a knick (bent-neck) F-Bass (or Bisset, sometimes called regular bass) for a few tunes. Compared to my smaller recorders, these two larger instruments can be like trying to blow up an elephant from his trunk. There are actually about five sizes of bass recorders, with mine being the smallest. Some bass recorders are a full two-octaves below my Bisset. Here's a great video demonstrating the Royal Wind Music's (Amsterdam) huge subcontrabass recorder standing at 10-ft tall! I teach both traditional and folk/Irish recorder styles.  D Tin Whistle (2006), D Low Whistle and G High Whistle (2020) The modern tin whistle (also called penny whistle or Irish whistle) is from a wider family of fipple flutes which existed in almost all primitive cultures. The block in the mouth piece that forms and guides an airstream to produce sound is called the "fipple". Fragments of 12th-century bone whistles have been found in Ireland and an intact 14th-century clay whistle was found in Scotland. Wooden tin whistles started to show up in the 18th century. An English builder, Robert Clarke (company still exists today), pioneered the use of soldered tin sheets to mass-produce whistles starting in 1843, and even if made out of other metals or plastics today, they are still called "tin whistles." The tin whistle became very prominent in Irish music, and stylistic techniques borrow heavily from the bag piper community.  (Left to Right) Recorders: Garklein, two each Sopraninos, Sopranos, Altos, then Tenor and F-Bass Whistles: D, F, G, A and Bb Low Whistles, and a mess of C, D, Eb and high G Whistles I also have several Irish low whistles in my collection, love the warm, breathy sounds. They are a relatively modern instrument, invented in 1971 by Bernard Overton in England. Because they have the same fingering and ornamentation as regular tin whistles, just larger, they are characterized as an Irish instrument. Recent movies and stage productions such as Titanic and RiverDance have made low whistles very popular. One Christmas, Irma bought me a cheap mail order practice chanter. A chanter is the part of a set of bagpipes that you finger to play the melody. I wasn't convinced what we got was an actual musical instrument, and all I was able to accomplish with it was make dying duck sounds. I didn't have any more luck when I tried out a good modern phenolic practice chanter that the local pipe bands were recommending. Because it was yet again different fingering from my recorders and tin whistles and I've heard stories of maintenance nightmares from folks who play various small pipes, I've put off pursuing such for the time being. |

Other Things You Blow Into Harmonicas, Train Whistle, Slide Whistle, Bamboo Flute, and Ocarina The Chinese are credited with the invention of free reed instruments, and their sheng made of bamboo tubes and flexible metal flaps dates back to around 1100 B.C. A free-reed is an element of a wind music instrument where flexible reed(s) made of bamboo, metal, or plastic are fixed at one end and vibrate freely within a close-fitting frame under pressure or suction. The more immediate forerunner of the contemporary harmonica was invented by Dutch physician and physicist Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein in 1780. Evolving through instruments such as the harmonium, the pocket-size harmonica (mouth organ) arrived in the 1820s and spread throughout Europe and the United States. The famous German harmonica maker, Matthias Hohner started his music company in 1857, finding a huge market in America. Between world wars, harmonicas appeared with vaudeville acts and Hollywood cowboys further popularized the delightful instruments. From there, harmonicas have found themselves in folk music, blues, rock and soul. We have a few in various keys, and have done music from time to time with some masterful players. |

Melodica and Concertina Melodica (2008), Concertina (2011) (Scott) My interest in accordions and other free reed instruments started back in junior high school with a gift from my mom. She always loved finding weird things at garage sales, and one day she presented me with a busted up Hohner piano accordion in the original dilapidated case. With the typical enthusiasm and skill deficit of youth, I repaired it, and sometimes would pull it out for school friends to amaze them that I could actually play. Irma got tired of us lugging the ugly thing around early in our marriage, and sold it at a garage sale for $5.00. Perhaps 20 years later, we were shocked to learn that mom hadn't bought it at a garage sale. It was my great great grandmothers! Irma remarked that this would have been nice to know, and it just made for a better story. There are many different types of accordions, piano accordion (popular in the western world, both acoustic and electric), diatonic button accordions (expecially popular in traditional Irish music), chromatic button accordions (Eastern Europe and Russia, known as Bayans), Cajun accordions, melodeon (similar to a 2-row rish accordion but with only a single button row). A lot of accordion was played in 1940s cowboy music, and we had a tune in our cowboy band that we wanted that sound on. It's fun to know that before the electric guitar got going in early rock n roll, a young man could pick up girls in the 1950s if he could play accordion, they were heart throbs! Irma bought me a low end melodica to try out with the band. This is a late 1950's invention for the non-affluent, essentially the right hand side of a piano accordion that you play via blowing into a tube without the bellows or left hand chord/bass buttons. It get's some really fun reactions from audiences! Over time, it got more and more out of tune, and I really wanted something with the free reed sound where I could play and sing at the same time. I can't tolerate the weight of a suspended accordion anymore, so I started researching what other instruments might work. I read about concertinas with increasing interest. They were real common in the mid to late 1800s, started to fall from popularity around World War I, then began being played again during the 1960s/1970s folk revival. I mentioned above our inadvertent selling of my great great grandmother's accordion. One day I told mom I was researching concertinas, and she told me she remembered my great Aunt Elizabeth saying my great great grandmother also played them. That cinched it, in memory of her lost accordion, I had to start playing concertina. There are two primary kinds of concertinas, English and Anglo (also called Anglo German). English concertinas were the more refined and expensive instruments in history, and played the same note whether you pulled or pushed the bellows (called unisonoric). Anglo concertinas were played more in social music, and is the kind still played most in Ireland. Besides getting a different note when you push or pull the bellows with the same button depressed (bisonoric), melodie notes cross from one side to the other as you play buttons on both sides. You play harmony notes or chords by depressing more than one button at the same time. This was the kind I wanted to play. The Victorian age was very interested in technology and mechanisms, and things invented in that timeframe where often very complex, perhaps overly so. Sir Charles Wheatstone was credited with the invention of the concertina in 1829. Those of you who studied electrical engineering will remember the Wheatstone bridge, a way of determining an unknown electrical resistance value - same guy. A concertina ends up having hundreds and hundreds of moving parts, and the passing of time can be unkind to old instruments. I encountered a problem in that there are only a handful of concertina builders throughout the world. New instruments are really expensive with waiting lists measured in years. One-hundred-plus year old used ones (even ones that were junk in their day) are hard to find and cost gobs to recondition. Handmade concertina reeds substantially add to the cost of new and reconditioned instruments. To try to get a new generation of players going, in the late 1990's a few builders in America an England started making hybrid instruments with concertina designs and mechanisms, but with relatively inexpensive mass-produced accordion reeds. This brought the price down a lot, but still too much for a secondary instrument for us. So the search was on to find a used hybrid concertina in good shape. Through hours and hours of internet reading, I found The Button Box in Sunderland, Massachusetts, where Richard Morse's staff were building hybrids. They were wonderful to work with, and within a few months of my initial contact, they got hold of a used hybrid they built in 2000 in the keys and fingering I wanted. It had lived in several places around the country, and they reconditioned it to good-as-new shape for me. It took a long while to get up to speed with it as I personally didn't know anyone who played Anglo concertina. I since met a great elderly woman in Arizona (friend of a music friend in Colorado) that plays, and we got to play together for an afternoon in 2011 when they were passing through Albuquerque. She has since passed, but I will treasure our "concertina" afternoon together forever. |

Piano and Keyboard Korg Synthesizer (Irma 1990) (Irma) When Dad retired, we settled in a small town in south central New Mexico, Socorro. It's a college town, with the bulk of the population having something to do with New Mexico Tech. When I was in junior high school, one of the college students was going home back east for the summer, and needed to store her piano. My family offered to have it at our house. The piano was an old blonde upright, a little worse for wear. But that instrument opened up a whole new world of music for me. Up to that point, I knew very little about music theory, reading music, scales, or anything other than playing and singing by ear. I started noodling around with it, figured out how to play guitar chords on the piano, and began to plink out melodies. The first song I learned to play with two hands (ooooooo!) was Nadia's Theme. Not because of the Olympic gymnast, but because it was the theme song to The Young and the Restless, a soap that I had started watching with Mom. I can't believe I'm actually admitting to having ever watched a soap. Nevertheless, the song was beautiful, and I had found yet another instrument to accompany my singing. Unlike the guitar, I found I could play in keys such as F, Bb, and Eb with ease. For the first time, I was playing with written music, as long as it had guitar chords! From that point, I was able to learn to decipher printed music: keys, time signatures, treble and bass clef. The mystery of music theory had begun to unravel. When Scott came to New Mexico Tech, he wanted to bring his electric piano, but didn't have space in his dorm room. As he was playing in my band, once again I offered to have it at our house. I didn't give it back to him until we were married. In the years since, I've played a lot of piano leading choirs, congregational singing or during choir rehearsals, and do some duet or ensemble numbers with me on piano or keyboard.  Piano (Scott in High School Stage Band 1977) (Scott) I grew up with three older brothers. As was the custom in those days, we had a family piano that was essentially a big piece of furniture to dust. (My mom's mother was a concert pianist, but it didn't rub off on mom.) Back then, mom said when the other boys sat down at the piano and messed around, it just sounded like noise, but (ta da!) when I sat down, it sounded like music. (In later years, one of my brothers played some guitar plus piano by ear, and another brother some nice blues harmonica and guitar, but neither ever performed.) Because mom had a close friend that was an organ teacher and not piano, they bought me a Thomas Color-Glo organ (novel feature for beginners where the keys could be lit up from underneath, revealing note names and chord patters), and I started lessons when I was four years old. For the first few years, I was so small that to play the pedal board, I had to wrap my right leg around the front stool leg to keep from falling off the bench when I stretched my left leg down to reach the pedals. I played a lot. Sometimes mom would ask if I wanted to stop and go outside and play with my friends (did that a lot anyways), and I didn't understand - I was having fun! When I got into junior high school, I started playing high brow pipe organ in liturgical churches. Anywhere I went then, they had pianos but not organs. About the time I began getting into jazz, I started playing piano in addition to organ. In high school, I played a Fender Rhodes Mark 1 Suitcase 73 electronic piano in stage band (made popular by players like Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Bill Evans, and Stevie Wonder), and my dad bought me a used 1960s Wurlitzer Model 140B electric piano (Karen and Richard Carpenter toured with one of these) that I used in bands. College was so intense (engineering) that I was able to keep up lots of guitar and singing, but piano fell by the wayside after one semester of stage band. I had dreamed for years about owning a synthesizer (now, we just call them keyboards), and approaching a decade of marriage, we finally bought a Korg DW-8000 synth that used the analog voice paradigm which I had dreamed of owning for years. We went through our electronic stage or midi stage of music, where we played a lot of synth and electric guitar. I also wrote numerous computer programs to control the synth and manage sound libraries. Every once and a while I'll sit down at the keys and play for my personal enjoyment or just to show someone that I can, but it will be some future time I suspect when I get bit by that bug and start to perform again for real. |

Marimbula Marimbula, Two rows of wood tongues (Irma 2008) At a point in time, our original upright bass player in our cowboy band, Wing & a Prayer, left to do other things. We had to go about 6 months without a bass on the bottom end which really left the music lacking. I don't know if you live in a place where acoustic bass players grow on trees, but here in New Mexico, they're so rare we know some bass players that are in 3 or 4 different bands at the same time. In the timeframe we were looking for another bass player, we had gone up to Fort Collins, Colorado, to the dulcimer festival there. We walked into a large room where a bunch of folks were jamming, heard the nice bottom end of a bass thumping away, and scanned the crowd to locate the player. There wasn't a bass to be seen! What we did see was a funky tongue drum thing that looked like a mbira on steroids (Irma calls it her alien pod). We couldn't believe that in the ensemble setting, it really did sound like an upright bass. Hmmm, don't need a semi to cart it around, and no learning curve for a fretless instrument. We came home from that trip thinking there might be hope yet for our band getting another "bass" player. Thus began our research into bass boxes, often called rumba boxes. We found that they are usually square in shape (like a suitcase), with metal tines, and you sit on them to play. Scads of cultures have things like this. Normally, they only have a single row of tines, giving you barely enough notes to get by. Irma loved the two-row chromatic instrument we'd seen in Colorado because you could add walking bass lines to the standard boom chuck, and play in any key. We ultimately contacted Michael C. Allen of Cloud Nine Musical Instruments in Ohio, and purchased one of his 13-note models (he calls them marimbulas, and has a nice write up about them on his site). Possibly unique to his instruments, he uses wood tongues (ash, like baseball bats) rather than metal tines. He makes 7-, 9-, and 13-note versions, and also builds hammered dulcimers. While he says folks normally play it like a regular rumba box with it perched on the ground vertically (he can even install an adjustable bass foot peg to raise the note tonges closer to the player's hands), we did like we saw in Colorado and set it on a hammered dulcimer stand so we could face the audience and sing at the same time. It's very easy to get started with. We've taken folks that have never played any kind of bass before and had them going at it in a few minutes. Like any instrument, with some time investments, one can get pretty good with it. It got a full-time workout in our band for years where Irma's brother-in-law normally played it, we use it for a few of our tunes in our duet and Irma used it for some tunes on her albums. |

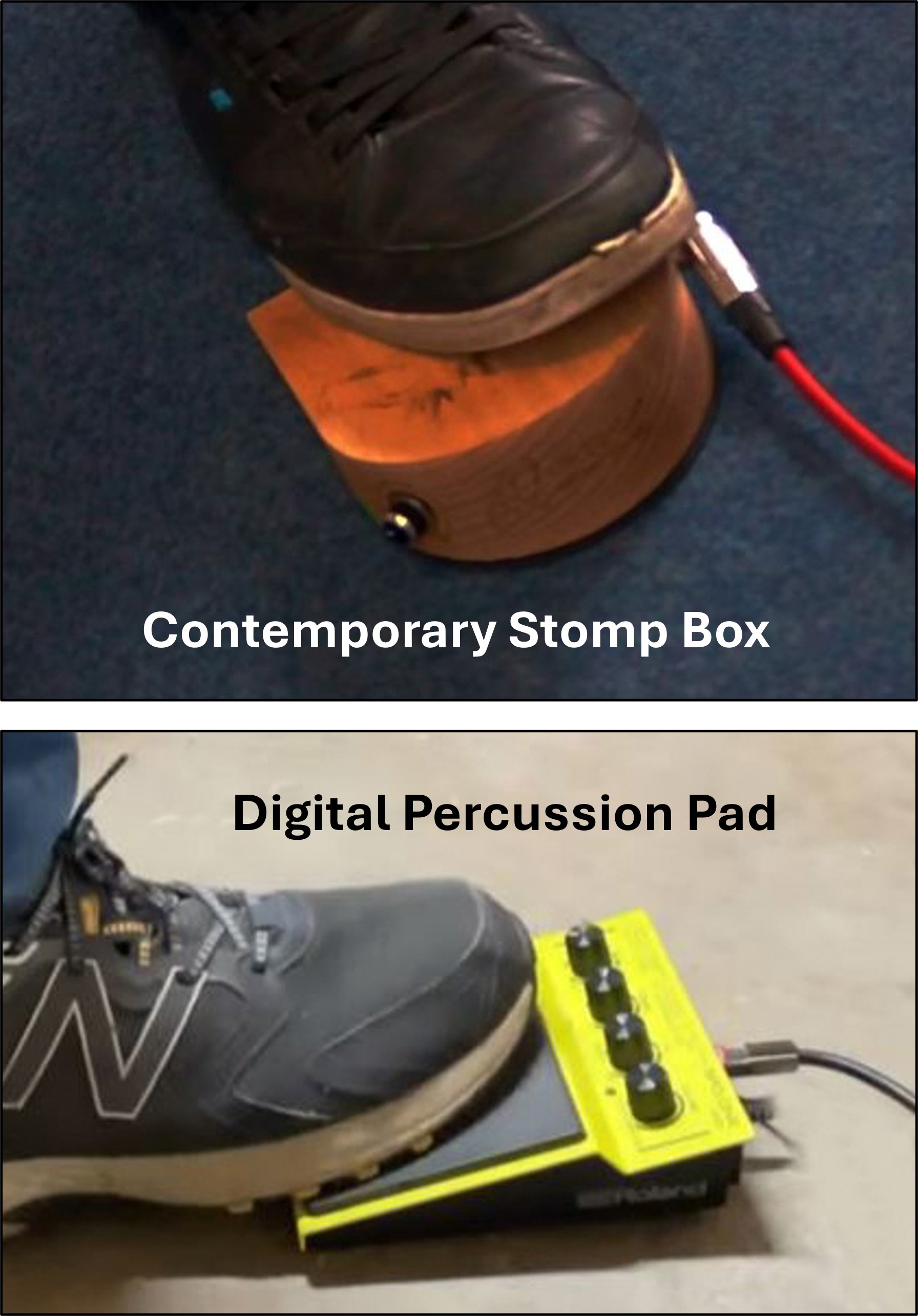

Bodhrán(Irma) I was a frustrated drummer for years. As a young teen, someone once told me that "good girls" didn't play the drums. I was too young to follow up on that theory at the time, but the love of percussion has always stayed with me. Tambourines, wood blocks, egg shakers, maracas, claves, bar chimes, even a fly swatter on cardboard (makes a great percussion instrument! My band thought I was nuts). I've always enjoyed my forays into creative rhythms. With a jazz background, Scott also loves percussion and plays some.  Irish Bodhrán (Irma 2006) It was at Apple Mountain Music store in Albuquerque where I found my harp that I also found the bodhrán (Irish frame drum). A frame drum is a hand-held drum where the drumhead diameter (the stretched membrane) is much greater than the drum's depth where the short drum shell (the wood cylinder) does not add appreciably to the sound resonance. Intrigued, I studied music videos, watched different styles, listened to rhythms, even took a workshop. What fun! It's so dry in the New Mexico desert, I had to moisten the goat skin drum head of my first bodhrán on stage with a water spray bottle before I performed so it would loosen for a good, deep sound. I told audiences I had to water my goat! On a few occasions, I overwatered my "goat" which resulted in only a dull thud - we'd have to play another song while my drum dried out a little before we could play the intended tune. To eliminate this risk and hassle, I eventually bought a bodhrán with a tunable head where I no longer have to mess with watering it before I play. Nothing gets the toe tapping and blood pumping like the bodhrán, except, perhaps, bagpipes. But that's for another day! You can hear me play bodhrán on all three of our albums. Stomp Box(Irma) For live performance, we have a few tunes worked up where Scott will play a fast jig or reel and I'll back him up on bodhrán. It's a lot of fun! In the recording studio, I can do a lot more; for the same song I can play an instrument then overlay bodhrán or other percussion on additional tracks. We wished we could do this in live performance. One year when we were at the Walnut Valley Festival in Kansas, the traditional Irish band Socks in the Frying Pan blew us away when a member started tapping his foot and a huge bass drum sound was added to their performance. They were using a device called a percussion stomp box. We fell in love with the idea. Stomp boxes have become quite popular, especially with solo guitarist/singer acts. They can be quite simple, or very complex with a virtual full drum kit played by the feet.  Stomp Boxes (Scott) While a few different technologies are used, most stomp boxes use a piezo-electric transducer to convert the foot impacts on a wood block or resonator into an electronic signal. A preamp and possibly other onboard electronics tweak the signal which is then sent to an amplifier or PA system via a standard 1/4" guitar cable. A lot of different acoustic instruments use pickups employing piezo transducers. We reviewed many contemporary stomp boxes but were often left underwhelmed. While radical mixer setting changes could come up with better sounds, we were not satisfied. The bodhrán can produce a really big sound which we wanted to emulate. The other class of percussion stomp boxes are purely electronic (often called drum pads). Like many modern keyboards and other instruments, they use digital recordings of actual instruments (called samples) to reproduce genuine sounds. We went with a Roland SPD-One Kick floor pedal. Included in its 22-sound library (things like cabasa, guiro, claves, cowbell, hand clap) are five glorious kick (bass) drums! We can adjust the pedal sensitivity, even change the pitch and add reverb or distortion. Irma has used it for both in-person performances as well as Zoom concerts. She's even used it in the recording studio to layer with acoustic drums. |

Hardwood Tongue Drum Hardwood Tongue Drum (Irma 2011) Many cultures made hardwood tongue drums (or slit drums) where slits are sawn out of a wood plank or hollowed log to form the sounding tongues (or keys). They are thought to have originated as a ceremonial drum with the ancient Aztecs in central Mexico. Their drum, called Teponaztli, had two slits on the topside cut into the shape of an "H". The resultant keys were of different lengths providing nonspecific high and low notes usually a third or fourth apart. Keys were struck with mallets or deer antlers. (Scott) We scheduled the music stage at the annual Weems Artfest in Albuquerque for several years where you can see all sorts of paintings, sculptures, photography, clothing items, even custom furniture. One of those years when we were walking around to see what there was to see, we heard the most beautiful musical sounds coming from the far end of the extensive exhibition space, easily carrying above the den of hundreds of gabbing art lovers. It sounded like a marimba, yet different. We followed our ears to find Michael and Joah Thiele's hardwood drum display booth, and looked with amazement to see these wooden instruments, some no bigger than a small shoe box. They also make large bass-register instruments built into coffee tables with remarkable tone, and have done multiple station instruments built into a single dining table. We couldn't believe how wondrously the notes carried, and how well tuned the instruments were. We'd previously seen hollowed out logs and such using this principle, but never with such pitch precision nor tonal beauty. Following the careful slit cuts, they use a Dremel tool on the bottom of each tongue to remove small amounts of wood to bring it to good pitch. We discussed their drums with them at length, and between the four of us, probably played every instrument they had on display. Over the next many months, the beautiful sounds kept gnawing at us. We identified numerous tongue drum builders in the US, with the Theile's work most highly regarded. We placed an order with them inside of a year for a 12-note model, Caribbean tuning, in the key of D (using a standard 440 Megahertz tuning standard). They normally make this size of drum in the key of C, but to be played in ensemble with our other folk instruments, the sharped key of D gives us more options. From being able to try out lots of their instruments from our first meeting, we selected African Padauk for the soundboard and Santos Mahogany for the sound box. Joah told us the mahogany came from the floor boards of an old torn down building. After a year of playing ours where the instrument could settle in to our climate, we sent it back to Joah where he did a tuning touch up which remains spot on today. Every time we've seen the Thiele's since, they show us more examples of their art, all sorts of new and intriguing tuning schemes, different woods, shapes and sizes. If we were rich and famous, we'd have no problem finding a bunch of these to bring home. Irma usually plays it with four mallets (two each hand) so she can get interesting chords. I play it with the bottom surface of my fingers like paddles where striking each corner activates three notes generating various chords. |

Steel Tongue Drums Steel Tongue Drums Based on ancient wooden slit drums, the steel tongue drum is a relatively new invention. Initial versions were made from propane tanks in the 1980s in Africa, thus they have also been called tank drums. The modern steel tongue drum is credited to Dennis Havlena (Michigan) in 2007. He called it the hank drum (a combination of the hang drum/handpan and the tank drum) which was inspired by two notable predecessors: the whale drum (Jim Doble/Maine in 1990), and the Tambiro (Felle Vega/Dominican Republic in 2007). Vega highly popularized steel tongue drums via the internet. Steel tongue drums fall into the idiophone class of music instruments where the sound is primarily created by the vibration of the instrument itself without being blown or using vibrating strings or membranes (such as drums). Specifically, they are struck idiophones as they can be struck with your hands which can engage more than one tongue with each strike if desired, by individual fingers, or with mallets. (Scott) We listen to lots of Youtube videos and are intrigued by all sorts of music instruments. I had been fascinated with the soft and entrancing sound of steel tongue drums, a very different character than our hardwood tongue drum. Musical tones from individual tongue strikes sustain for a very long time leading to complex frequency interactions which generate very emotive textures. We like the Idiopan brand drums (invented by Bret Hutchinson in 2010) for their beautiful tone and the ability to reposition magnets on the underside of each tongue to fine tune or retune individual tongues. We've grown to two drums, 8" and 12" sizes, each with 8 tongues, which can be put into complementary tunings. |

Drum Kit Drum Kit (Irma 2020) The drum is one of the oldest instruments in human history. Immigrants coming to America in the 19th and early 20th century brought their various percussion instruments with them. The modern drum kit, an American invention, is the result of this cultural mixing and subsequent drum evolution. In the 1860s, bands started experimenting with multiple percussion instruments, combining them into what was then known as a trap set. A drummer could play the bass drum and snare drum with sticks while using a pedal to control a pair of cymbals (called a low boy, predecessor to the modern hi-hat). During the 1900s, companies like Gretch, Ludwig, and Slingerland began developing commercial drum sets which included bass drums played by pedals. As the drum set evolved, tom-tom drums based on traditional Chinese and Japanese cylindrical tuned drums were added, and woodblocks, small cymbals, and other special effect percussion instruments were added for musical theater or silent movies. Continuing his family's cymbal manufacturing tradition begun in 1618 in Constantinople (aka Istanbul), Turkey, Avedis Zildjian III established the first mainstream cymbal company in America in 1929. Working with drummers of the 1930s and 1940s (Gene Krupa, Chick Webb, Jo Jones, Buddy Rich, etc.), Zildjian went on to invent the collection of popular cymbal types used today: crash, ride, splash, sizzle, and hi-hat. By the 1940s, swing drumming had evolved into a new form of jazz called bebop, with further evolution from large bands into smaller combos and ensembles. This led to the standardized drum kit we recognize today. As famous Rock 'n' Roll bands played larger venues, larger drum kits with more powerful drums (including the double kick drums) and a wider variety of drum sounds appeared alongside the established smaller drum kit. (Irma) For my 2020 album, Possibilities, I wanted to add a military snare drum cadence to my Travelin' Soldier track. As I gained skill playing the snare drum and messing around with cymbals, this led to adding kick drum, mounted and floor toms, plus hi-hat, crash, and ride cymbals. Before I knew it, I was playing a full drum kit in jazz and rock styles for some other album tracks. I had finally realized my dream of becoming a girl drummer! |